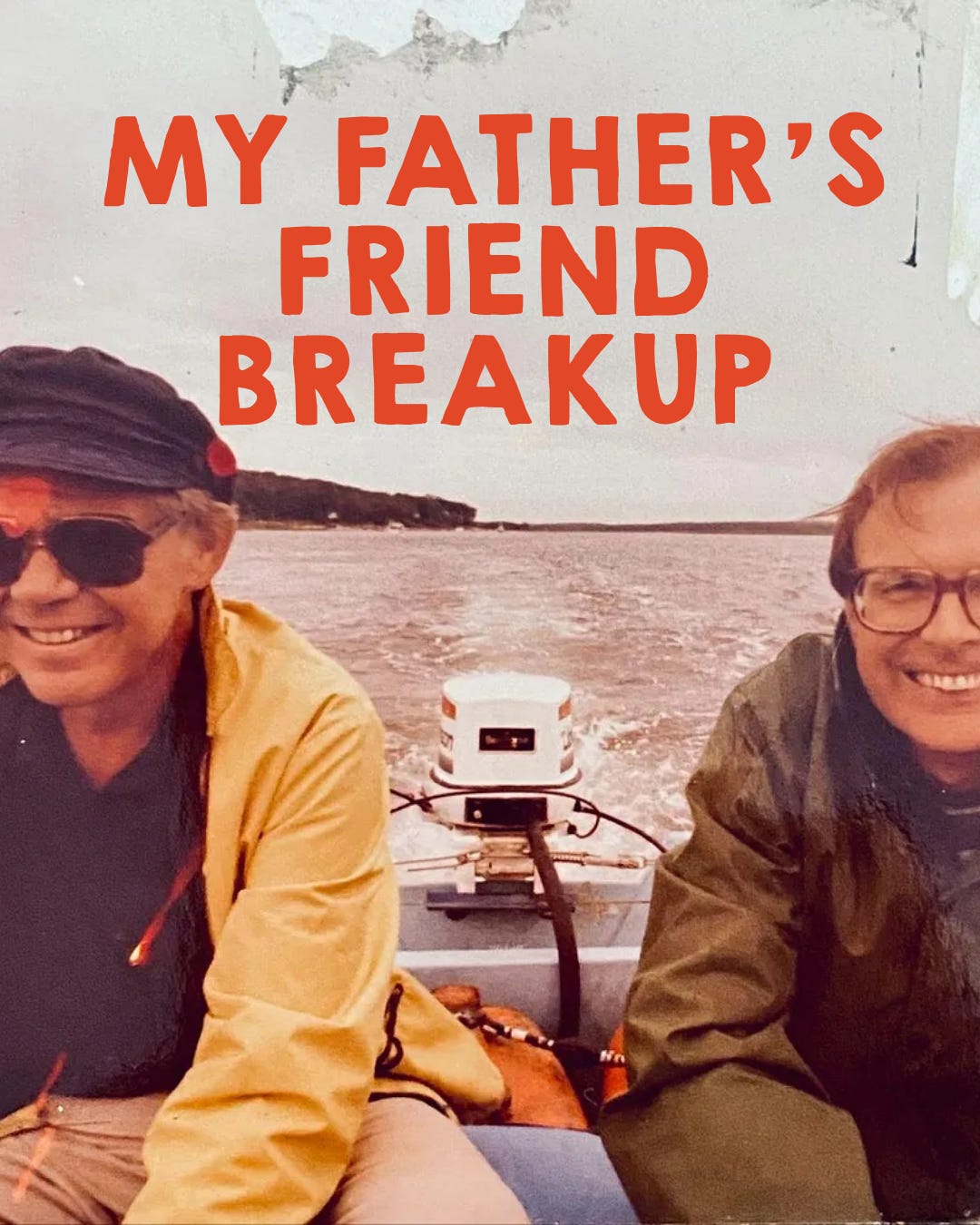

I used to think of Jack as Toad and my father as a Frog, from the Arnold Lobel books my father read to us as children. I love this photo because they both look so happy. Jack is in yellow. Dad is in green. Jack was thick set with a deeply furrowed brow that aged him even his early forties. My father was boyish and agile, with a forward tilt of the head that eventually gave him a permanent hunch in his upper back. The two of them balanced each other physically and emotionally. Dad was eager, enthusiastically leaning into everything with quick flashes of anger. Jack was a skeptic, and looked for pleasure no further than his cocktails (Manhattan on the rocks) and weekly game of bridge. My father had brief intermissions between long term relationships, including his early marriage to my mother, and later, to his second wife, though neither marriage endured. Jack never brought a boyfriend "home" that we knew of and once it occurred to me that he was gay (sometime in my early teens I put the pieces together) it was not from observing any romances. It was as if you had suddenly noticed the view from his living room that had always been there, along with his wry assumption that life was an essentially hopeless situation. They had grown up together in Fall River, Massachusetts, a city best known for the Lizzie Borden murders, where empty textile factories still line the highway to Cape Cod. As boys they would have recognized each other as funny and smart, my father playing in the treble clef and Jack the bass. Jack was a constant presence on the “divorced dad” vacations we spent in various summer rentals they shared on the shoreline south of Fall River. They eventually bought vacation cottages only steps away from each other, and a 26-foot fiberglass sloop they named the “Tontine.” A tontine is an 18th century term for a bet or legal contract. Whoever died last got the boat—and won the bet.

Everything changed when they were in their mid-sixties. By then, all three of my father’s daughters were grown. There were no more long games of Uno and Monopoly. The boat had been sold. But they still spent their summer vacations on “the lane” where they had bought their houses on the river. One summer visit, I noticed that my father wasn’t going over to Jack’s for their evening cocktail. I asked why not, and he said that he didn’t really know. It was no secret that Jack didn’t like Dad’s new partner. Jack was touchy and she wasn’t always easy. It wasn’t hard to imagine that Jack had somehow been offended. But my father’s girlfriend was hardly ever on the lane. She had a summer house on one of the islands off the Cape where she and my father had a social life that was an extension of the publishing world they shared in New York. Jack wasn’t invited to join them on Nantucket, but what did it matter? He was recently retired from his own esteemed career as a professor at Georgetown, and wouldn’t have gone anyway. Have you talked to Jack about it? I asked my father. I can’t, he said. I could tell he was afraid to. I walked down the lane to say hello to Jack, who gave me his usual big hug and asked about everything in my life, my kids, my work.

I was afraid to ask him too.

When I came back up to the house, I talked to my father again. We were very close and talked about everything. Would you like me to sit down with the two of you to help figure this out? No, no. He changed the subject.

Finally, Linda, another childhood friend who lived at the top of the lane (I know, it really does sound like Frog and Toad) marched down to Jack’s house and told him that he had to stop being so angry at Jimmy—only his Fall River friends called him Jimmy. The two of you are being ridiculous! she said.

Seven years went by.

My father spent less time at the summer cottage unless we kids were visiting. I brought the grandchildren, my sisters came, but Jack never joined us on the porch for drinks and dinner anymore. When I visited, he would invite me out to lunch for a lobster roll, just the two of us. I wanted to see him and felt guilty to be there without Dad.

My father had a heart attack at seventy-three. He was there and then he was gone. The center could not hold without him. Jack was as broken as any of us. When he spoke at the memorial looking out over the harbor where they had moored the Tontine, the paper for his eulogy trembled between his square, strong hands. I don’t remember what he said, only the Billie Holiday songs they used to sing along to drifting out onto a perfect blue day. Jack could barely speak. He had won the bet.

Later, Linda said to me, over cocktails on the lane, that she thought Jack had always been in love with my father. She said he had waited his whole life for the two of them to grow old together down by the river. But they aged differently, she said, leaning in to be sure I understood her. Jack embraced old age and your father ignored it, pretending that he would never get old. Nobody could believe he was seventy-three! She added, smiling, her own face now lined and freckled with age spots. Jack never expected that last big affair, she said quietly, and it infuriated him,

I don’t know if Linda was right. It could be true. She had known them both longer than I had. I don’t know what my father would have thought of her theory. He might have agreed. He might have laughed it off. Two years later, Jack died of cancer in a hospital in Fall River. We never spoke about the seven years of heartbreak between them.